Art worlds: Interview with Eleanor Heartney

March 19, 2014

The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium (Prestel, 2013) is the second literary offering from the co-authorship of Eleanor Heartney, Sue Scott, Helaine Posner and Nancy Princenthal, which focuses on women artists’ contribution to 20th-century art from the 1970s onwards. Alongside the first book, After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art, the works form an extensive exploration into the evolving position of women artists, drawing on statistics, exhibitions and art schools. AMA had the opportunity to interview Eleanor Heartney who, for her own part, is an independent cultural critic and author living in New York. Her career has included contributions to numerous publications, including the New York Times and the Washington Post. We asked her for a deeper insight into the main issues raised in the books, and if the team have any future plans.

The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium is your second publication focusing on the influence of women artists in the 20th century. Can you give us a quick overview of the book?

First of all, it’s necessary to talk a bit about the first book (After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art) in order to get to the second book: it was an overview of contemporary artists, looking at twelve women who were doing all manner of work and the book sought to answer a question which was asked many years ago by the art historian, and one of our guiding lights, Linda Nochlin in her landmark essay “Why have there been no great women artists?” Now, there have been! We had a great response to that book, which led us to consider a second publication. The first book was a very broad overview with intensive essays on each of the twelve women artists, and we thought that it would be interesting to look more exclusively at younger women, whose shorter careers meant that the essays were not so extensive. We also wanted to be more international than in the first book, because it was something which we felt was necessary to reflect what was really going on in the contemporary art world. Considering the organisation of the book, we hit on four themes: “Bad Girls”, “Domestic Disturbances”, “History Lessons” and “Spellbound”, two of which were quite personal and internal and the others more social and outward-looking. Given that we all have a background as art historians and curators and we are interested in how feminist art came into prevalence, we wanted to link these women to the groundbreaking women artists of the 1970s, so we came up with the idea of having a godmother image for each of the four chapters, which allows us to talk about the changes which have taken place in the feminist art movement since its emergence in the 70s. This gave us the opportunity to explore the continuities with the past as well as to demonstrate how things are different now. More generally, it was an attempt to figure out where art, not exclusively women in art, is today.

How did you decide on the four chapters?

I’ve always had a great interest in bad girls, so I knew from the outset that I wanted to do this chapter, and each of us took a chapter that we felt in some way very connected to. “Bad Girls” was of particular interest to me because I have long been interested in this paradox of feminism and women’s relationship to their bodies. I wanted to address the possibility of doing work about your body without becoming a part of the male gaze. Women artists, even back in the 70s, were very interested in the tropes of pornography and these transgressive modes, using them as a way to break through a lot of our attitudes about what women’s desire and sense of their own body should be. In some respects there is less controversy in using your body in this more erotic way now than there was in the 70s: a lot of the women artists who did it then got into big trouble. There’s still a backlash, within and outside the art world, and it comes from both liberal and conservative sides. It’s a very potent and interesting issue and it served as a way to explore a lot of other ideas.

The working title for the book was “Taking Control”; why did you decide on this title originally?

We were thinking again about younger women, and we questioned what changes have taken place. The notion of “taking control” was a very optimistic title and as we began to think about it we decided that it wasn’t so clear cut: our statistics continue to prove that, certainly within the wider art world, women are not reaching parity with men. With this in mind, “Taking Control” seemed overly optimistic. We went through a lot of titles, and then finally Helaine [Posner] reminded us that, in Linda Nochlin’s introduction to After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art, she introduced the idea of “after the revolution”. Helaine said, “After the revolution comes the reckoning,” and hence we found our title.

We are seeing an increasing trend for art prizes aimed directly at female artists, such as The MaxMara Art Prize for Women and the Theodora Niemeijer prize. Do you think these prizes are necessary to provide female artists with sufficient exposure?

I do, and I would add another really great prize called Anonymous Was A Woman. People always question the need for an all-women book, show or prize, and that’s one of the main reasons why we collated the statistics, to demonstrate that, despite our preconception that things are improving – which they are overall – they still aren’t as good as you might imagine. In fact, the statistics surprised us; women’s representation hovers around 25-30% in all the major markers. If you look at the US Senate you get these same statistics. That’s why we feel that it is very important to continue to produce this manner of women-orientated activities, because there is clearly still something which is holding women back from parity with men in many of these areas.

How did you collate those statistics?

We had to decide what areas we wanted to look at: in The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium we wanted to look at art schools, because it is often said that the proportion of women coming out of art school to those who go on to succeed in the art world is comparatively low. We analysed major museum shows, galleries and art schools which we felt were representative of the wider trends. We are not scientists, but we did our best to use the statistics in a way which would give the broadest view of what was happening: our surprising findings have meant that the statistics are definitely one of the most noteworthy parts of both books.

In your 1997 critical essay, “Out of the Ivory Tower, social responsibility and the art critic”, you write that “the art world is very good at examining problems, but not very good at doing anything about them”. Do you still feel the same way about the art world today? What are the major problems faced by today’s artists?

It’s interesting to look back at things that you have written and I still support a lot of what’s in that essay. However, I think that you have to talk about “art worlds”, rather than a singular “art world”, these comprising varying degrees of public exposure. The most visible art world is that which we address in our statistics; the big institutions, the market and all of these large organisms which move things forward; you could call it the “art machine”. But the market is a significant factor in this main art world, and this meant that our own statistics used the market as one of the key markers. We have to consider that there are other art worlds which comprise their own figures, but which are not necessarily represented in the market. One possible reason for women’s lower representation in the market is that it simply doesn’t interest some of them: they are concerned by other things. There is a very dysfunctional quality to the art world right now, which is linked to the enormous influx of money and the focus on established figures. I think this trend reinforces a lot of the biases in terms of the artists who are represented by the market. I think many of us in New York are appalled that the next big show at the Whitney is going to be Jeff Koons [laughs].

Thinking about the art worlds on the periphery of the market-orientated, sceptical art world: one of the things that I’m interested in right now is the issue of art and ecology, and I think a lot of artists – particularly women artists – are doing some very interesting work. It’s an area I am hoping to explore in the next book.

You also speak a lot in the book about video art and how it was not necessarily taken seriously in the beginning, perhaps because of its association with women artists. How do you think this format has evolved?

Video art is an interesting medium because it started out as an alternative to the object-oriented market – something which couldn’t be sold – and now we have enormous, very expensive, installations. Video, like everything else, has totally evolved. In the early days there was more room for freedom in these areas because there was no scrutiny of the market. At this point, both men and women were involved and I think they found it to be a very friendly domain. For women, it was liberating, because they didn’t have to worry about men artists saying, “Well, she paints well for a woman.” These were brand new fields, so they could really go in there and make their mark.

Several of the women artists whose work you explore in the book come from diverse cultural backgrounds; do you think female art from these countries is more poignant, given their unstable history with gender equality?

I have always been interested in oppositional art, or art which needs something to resist. I think one reason for the power of women’s art or feminist art is its resistance to a patriarchal order. I have always been interested in Soviet art – the unofficial art of the Soviets – and now I think there are a lot of interesting advances in the Islamic countries, many of which are being led by women. The fact that these artists have to push against a deep-rooted theme can make for very powerful art, and it brings with it a certain danger. If you’re an artist having to deal with these issues, you have to find a language which says what you want to say, but also somehow gets through the apparatus so you aren’t totally crushed by it. Opening up our analysis on an international level liberated us to talk about this idea.

One of the artists in “Bad Girls” is Ghada Amer, an Egyptian artist who creates pornographic images behind veils of threads and embroidery. The work is often discussed in terms of the Islamic veil, insofar as she is veiling female desire; however Amer has said that she isn’t just talking about herself as an Islamic woman, but is addressing the issue on a more general basis, having lived in the United States since 1995. She has a sense that there are social walls that, as a woman, you are not supposed to breach. This exploration of the forbidden and the criticised is integral to “Bad Girls”.

What direction do you think art by women is moving in now?

Thinking about art by women, as opposed to feminist art, women artists are doing all the stuff that everybody else is doing; so it’s hard to pinpoint. I do a lot of lecturing about art generally today and I always make the point that there are many art worlds, directions and narratives that people are involved in and themes that they are exploring: Eco art is one and participatory art is another. Sue [Scott] is also exploring Abstraction, because there are a lot of very good female Abstractionists. We are not suggesting that the artists we feature in our books are the only important women artists: by taking a thematic approach to our work, our intention is not to create a new canon, but to follow these threads that we consider to be of great significance in what they tell us about where we are in a much broader cultural sense.

Feminism’s Long March

By Abigail Aolomon-Godeau

Art in America, June 2007

Pg. 63 Vol. 95 No. 6

All of a sudden, or so it seems, work by women artists is everywhere to be seen. Well, maybe not everywhere, but with “WACK!” currently on view at L.A. MOCA and “Global Feminisms” at the Brooklyn Museum, women artists—many still among the living—are now showcased in major museums on both coasts. A growing number of monographs and university courses are devoted to contemporary women artists, and art critics such as Holland Cotter of the New York Times have matter-of-factly acknowledged the centrality of feminist politics and feminist theory to much of the significant art produced since the 1960s. Related events, such as “The Feminist Future” (Jan. 26-27), the Museum of Modern Art’s first-ever public symposium on feminism in the arts, and a recent spate of one-person exhibitions and catalogues on some the the period’s key figures (e.g., Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois, Kiki Smith, Ana Mendieta, Valie Export) would seem to attest to the “success” of both women artists and feminist thought within the global emporium that is the contemporary art world.

Would this were so, as the authors of After the Revolution: Women Tranformed Contemporary Art (Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal and Sue Scott) carefully document in their introductory essay, the rise of women artists (leaving aside whether these are considered to be feminist artists or not) has been neither meteoric nor, evidently, unchecked:

Examining the number of solo exhibitions by women artists presented from the mid-seventies until the present, through a representative sampling of influential (commercial) galleries, we can see that the situation did improve until the 1990s, but that it appears to have reached a plateau. In the 1970s, women accounted for only 11.6 percent of solo gallery exhibitions. In the 1980s, the percentage of solo exhibitions by women crept up to 14.8 percent, and in the 1990s the number increased to 23.9 percent, but the percentage has dropped slightly, to 21.5 percent, in the first half decade of the twenty-first century. The current number of solo exhibitions by women artists is not notably better than the average of women’s exhibitions for the entire period under consideration, 18.7 percent. While the number of women artists’ exhibitions has doubled since the early seventies, it has really only kept pace with an expanded market: women still have roughly one opportunity for every four of the opportunities open to men.

The authors also indicate that in the realm of art publishing, the number of monographs devoted to women artists is significantly lower than that of books and articles dealing with male artists—three publications on men to every one devoted to women. Although unmentioned, prices attained by women artists are also roughly lower than those commanded by male artists, and it is a rare group exhibition that features more than 18 percent women artists. This seems especially true in Western Europe, where many curators and writers remain dismissive of anything that smacks of “American-style” feminism—an attitude particularly evident in the composition of large-scale group shows and in art criticism historicizing the 1980s.

This is not however, to deny the important gains that women artists have made since the 1970s. After all, Janson’s History of Art was an all-male preserve until integrated in its third edition in 1984. Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer and Nancy Spero have in the past decade represented the U.S. at the Venice Biennale. Cindy Sherman can certainly be reckoned among the most famous of the living artists, and many recent survey books dealing with contemporary art include sections, if not chapters, on feminism and its artistic influence.

How feminism is currently handled in generalist books on contemporary art is another matter altogether. There remain nagging questions not merely about the still-elusive goal of genuine parity for women artists but about nature, place and status of feminism in contemporary art practice and theory. (Does a workable definition of feminist critique even exist?) Moreover, there is still the challenge of positioning feminist art-making within a pluralist and increasingly globalized arena that is largely market-driven and often remote from the concerns of all but a tiny fraction of humankind.

Two recent volumes, both devoted to the work of women artists, highlight some of the tensions, problems and contradictions hovering around concepts such as feminist artist, feminist art, woman artist and critical practice. Although these issues are not directly addressed in either book, the instability or amorphousness of such terms when they surface in the texts indicates the writers’ uncertainty about their relation to the individual artist and the work she produces.

After the Revolution consists of a collective introduction by the authors and 12 individually authored essays on prominent women artists (Louise Bourgeois, Nancy Spero, Elizabeth Murray, Marina Abramovic, Judy Pfaff, Jenny Holzer, Cindy Sherman, Kiki Smith, Ann Hamilton, Shirin Neshat, Ellen Gallagher and Dana Schutz). Such a grouping seems implicitly informed by the requirement to accommodate “differences.” Artistic mediums are diverse (painting for Murray and Schutz, performance for Abramovic, installation for Pfaff and Hamilton, film/video for Neshat, and mixed mediums or photography for the rest). Age ranges widely (from the 90-something Bourgeois to the 30-something Schutz). Ethnicity and race are also varied (through the inclusion of one African-American, one Iranian and one Serbian). Each essay is constructed as an overview of a single artist’s production to date and includes discussion of her artistic formation and training, her formal and/or conceptual development, and her overarching themes, preoccupations and manner of working. Composed by experienced and knowledgeable critics and curators, all of whom are lucid and thoughtful writers, these profiles are uniformly informative, occasionally eloquent and especially insightful when examining individual works in the broader context of the artist’s oeuvre, in each case vividly evoked by the book’s copious illustrations.

In contrast, Contemporary British Women in Their Own Words, by Rebecca Fortnum, a painter and lecturer at the University of the Arts, London, is a far more modest affair. It consists of interviews with 20 artists, many of who are relatively unknown outside of the UK: Anya Gallaccio, Christine Borland, Jane Harris, Hayley Newman, Maria Lalic, Jananne Al-Ani, Gillian Ayres, Tracey Emin, Lucy Gunning, Jemima Stehli, Claire Barclay, Maria Chevska, Tacita Dean, Emma Kay, Sonia Boyce, Tania Kovats, Runa Islam, Vanessa Jackson, Tomoko Takahashi and Paula Rego. Here, too, there is a range of mediums, of ages, and of race and ethnicity. Each of the interviews begins with a photograph of the artist, but the book contains no other illustrations. We might ask, at the risk of tendentiousness, why the image of the artist is deemed more important than images of the art. And given the few resemblances (other than gender) between the artists in either of these two books, what determines why these particular women artists should be treated as an ensemble? Indeed, not a few of Fortnum’s chosen artists insist that they do not define themselves as feminists or feminist artists. In her introduction, Fortnum acknowledges that her selection process was not predicated on any unifying theme: “The artists were chosen to represent a cross section of practices from the UK’s art scene.” So the book is based on what for her is the self-evident interest of artists’ creative processes. “Articulate or otherwise,” she writes, “the mysterious relationship of an artist to their work can never be exhausted and is compulsive listening.” But given the type of generalized descriptions that arise in the interviews, this approach is not especially informative.

Writing in the foreward to After the Revolution, Linda Nochlin (who effectively inaugurated feminist art history in 1971 with her essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”) states that the logic of such roundups is twofold:

Contemporary women artists as a group need to be singled out for critical attention. This is partly because their work has been less studied than that of some of their male colleagues and partly because only by taking them as a group can the range and variety of their stylistic and expressive projects be understood. For it is difference rather than similarity that is as stake here.

Yet the differences that are fully acknowledged by Nochlin and the authors are precisely what make the joint presence of these artists appear almost random.

This in turn raises the long debated questions of whether art made by women constitutes its own category and, if so, what characteristics–either positive or negative—could define such a category. For all their dissimilarities, both books seem to posit that women artists as women artists may be grouped together in some kind of collective persona. Such a rationale informed the establishment in Washington, D.C., of the National Museum of Women in the Arts (“dedicated exclusively to the exhibition, preservation, and acquisition of works by women artists of all nationalities and periods,” according to its website). One would be hard put to connect a painter such as Elizabeth Murray to a performance artist like Marina Abramovic, a formalist installation artist like Judy Pfaff to an unambiguously political artist such as Nancy Spero, unless one privileges gender over all other considerations.

Unlike certain other anthologies consecrated to women artists (for example, Catherine de Zegher’s Inside the Visible, 1996, or Helena Rickett and Peggy Phelan’s Feminism and Art, 2001) neither of these books is informed by a perceptible parti pris, other than the authors’ esteem for the artists they write about. Nevertheless, the title After the Revolution, affirming that feminism was once revolutionary but also indicating that we are now in the “after” stage, suggests what some Z might call a “post-feminist” position. This is clearly not the authors’ intent, but the temporal locution—“after”—remains problematic. Insofar as we are currently witnessing a backlash against many of the gains of the women’s movement (reproductive rights in particular, should one need an example), one might argue that, rather than living in the aftermath of the revolution, we are still experiencing its unfolding. That entails the emergence of the counter-revolutionary symptoms, such as the term “post-feminism,” itself, no less than the proliferation of religious fundamentalisms of all stripes. By eliding the distinction between woman artist and feminist artist, by largely ignoring any question of the politics of art-making itself, or indeed the institutions (both discursive and material) of the art world, After the Revolution and, more parochially, Contemporary Women Artists demonstrate the limitations of the category “woman artist” in the wake of the cultural transformations fostered by modern feminism.

As Nochlin herself argued in her founding essay, the import of feminism for women artists and for cultural production in general does not reside in supplemental measures that serve an existing apparatus. The assimilation of more women artists into either canon or market not only leaves unquestioned the terms governing both but implicitly endorses the established structures of legitimization and the market determinations that underpin those structures. For this reason, the consideration of women as artists entails some consideration of the larger factors—psychic, social, economic and institutional—that shape artistic production, notwithstanding the fortunes of any individual. The issue of whether a woman artist defines herself as a feminist is now somewhat beside the point. What is far more important is what the work is doing, how it operates in its context, whether it exceeds, disturbs, destabilizes or puts in question its commodity status as trophy, decoration or fetish.

In this regard, the influence of feminist thought on art is by definition a critical, a resisting, a dissident practice. Not least of the collective accomplishments of women artists who emerged in the 1970s is their demonstration of the pervasive gendering of all aspects of art. Thus, while there is obviously no such thing as a feminist style or ( in any simple way) a feminist art, there is perhaps an art of feminism, a widespread, international, constantly evolving set of practices that—whether or not they endorse notions of feminine specificity, whether or not they seek to invent artistic languages for sexual difference—have collectively sounded the death knell for the universal subject, the universal viewer, the universal producer and a universal art.

In the final analysis, the laudatory goal of acknowledging the contributions of women artists has its own pitfalls and limitations. Just as the “difference” once attributed to women’s art has historically functioned to marginalize or dismiss it, so too does recourse to a celebratory and pluralistic agenda minimize the no less significant differences within women’s art production. Failing to distinguish between affirmative and critical forms of art-making, between “conventional” and post-studio mediums, or between politicized and apolitical agendas is to implicitly affirm that women’s art-making is distinctive merely because it has been made by women.

Review

May, 1, 2014

Choice Magazine

Page 1579

The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium, by Eleanor Heartney et al. Prestel, 2013. 256p bibl index ISBN 9783791347592 pbk, $39.95

The Reckoning is a jargon-free, very well-written volume from the "third wave" of international feminist art publications. It offers attentive readers another potential version of the historiography of feminist art—from Womanhouse, Judy Chicago, Miriam Shapiro, Lynda Benglis, and Lina Nochlin to the present. It is also designed and written to be the true sequel to After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art (2nd ed., 2013; 1st ed., CH, Jan'08, 45-2415). In addition to Eleanor Heartney, the contributors to both The Reckoning and the second edition of After the Revolution are Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal, and Sue Scott. Though this new book has 100 fewer pages than the second edition of After the Revolution, it is up-to-date with women's multimedia, performance art, installations, and photography. Feminist erotica abounds as several artists discuss working with pornographic sources. The Reckoning more than doubles the number of featured artists in After the Revolution to 25, with text, illustrations, and ample color reproductions. Featuring 11 graphs, it is arranged in four categories titled "Bad Girls," "Spellbound," "Domestic Disturbances," and "History Lessons."

Summing Up: Recommended. ★★ Graduate students and above.—M. M. Hamel-Schwulst, formerly, Towson University

Sue Scott on women artists getting into museums, feminism and her new book

By Kyle Harris

July 29, 2014

Katarzyna Kozyra, Cheerleader, 2006

For decades, feminists have challenged the art world to open up galleries and museums to women artists. While nominal progress has been made, many major institutions still show a disproportionate amount of work by male artists. This disparity is one of many reasons critics Eleanor Heartney and Nancy Princenthal and curators Helaine Posner and Sue Scott co-authored The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium, a profile of 24 artists that some have described as a new canon -- a term the writers resist.

In advance of their appearance at Anderson Ranch, Westword talked with Scott about the book, the state of feminism and the struggles and successes of women in the art world.

See also: Favianna Rodriguez talks sexual liberation, immigration, racial justice and art

Westword: Talk about what you're going to be doing at Anderson Ranch?

Sue Scott: I'm coming there with three of my colleagues. It's for the second book that we've written. This one is called The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium. This is our second time to Anderson Ranch. We came for the first time with our first book: After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art. That came out in 2008, and this book came out last September.

Talk about the book?

This book looks at 24 women artists born after 1960. We've divided them into categories of our making--not something that they necessarily say they fit in. We looked at four seminal exhibitions or occurrences or works from the feminist movement. Each of us wrote about that section, and we all divided the artists up and wrote about them, regardless of which section they were in.

For instance, Helaine Posner wrote "History Lessons," and her take off of Nancy Spero. Mine is "Domestic Disturbances," and my take off is Womanhouse in 1972, in Chicago, with Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. The section called "Spellbound" was written by Nancy Princenthal, and has a take off of Louise Bourgeois. And then "Bad Girls," which was written by Eleanor Heartney, is a take off the famous Linda Benglis ad in Art Forum.

What are the differences between the two books? What do you mean by artists of the new millennium?

We had met for a couple of years to talk about the format of the book. We knew it was coming out in the Year of Feminism, so we wanted it to be something a little bit different. With the help of our editor, we brought the first book down to 12 artists, each of which represented a particular aspect of work as important women artists. For instance, we included Elizabeth Murray, which we used for painting. But it maybe could have been Susan Rothenberg or it could have been Jennifer Bartlett. We included Marina Abramovic. We included Louise Bourgeois, Judy Pfaff, who we feel led the way for installation work, cultural installation.

That's the framework of the first book. We were also looking at position and aspects of power in the art world. One section of it looks at how much women are represented in galleries and monographs and museums. We looked from 1972 to about early 2000. The numbers go up from the 70s to 2000, but women have the opportunity for solo shows at roughly 20-24%. In the 70s, the number of solo shows that women had in galleries was something like 14%. In the 80s, it went up a little bit. In the 90s, it was at 23%. In the 2000s, it goes back down. We look at it decade by decade.

Art historian Linda Nochlin wrote the forward. The take off of this book came from her famous 1972 essay, which asked: Why are there no great women artists? The short answer is because there is not the institutional support, which is why we then looked at the institutional support of the artists, which varied from 17% to 24% solo shows.

Talk about the 2000s? Why did the number go down?

We have a theory. We didn't put it in the book, because it's just speculation. In the 90s, women solo shows went up. In the 90s, especially the mid-90s, the market was terrible. It seems like when there's a booming market, men have more opportunities in galleries. The 2000s, that decade was a huge boom in the market. But I don't want to focus too much on that.

Sometimes we show these charts and people get all revved up and jazzed about it, because it's something really tangible. You could sit around all day long and speculate about the equality of women in the art world today. When you look at the facts, you can see that it's not 50-50.

In the new book, we also look at the number of MFA students graduating. For instance, Yale has pretty much worked its way up now. Most of the schools have. It changes year to year, but on the average, 50% are female graduates and 50% are male graduates. Yet when they get out into the commercial world, women have a 20% chance of a solo show.

Where do art collectives fit within your analysis? Groups like the Guerrilla Girls?

We haven't looked into it. We contacted the Guerilla Girls early on about statistics, and they didn't have them. We're looking to our third book and are trying to figure out what the themes will be. Collectives might be a good thing to look at.

Let's go back to the second book.

We came up with these categories that tied the work of the artist back to these seminal themes of feminism. We put the artists in these categories. Some of them could have gone into a number of categories, but we happened to put them in the one. Just because we put somebody in one category doesn't mean they may or may not agree with it. Kate Gilmore is in "Domestic Disturbances," for instance, and that departure is Womanhouse. She wasn't even born when Womanhouse was done. She's been on the panel with us and talks about the influence of feminism, because her mother was of the age of Womanhouse and feminism.

In some of our early panels, we got criticized by some artists, because we chose to include women artists who didn't necessarily have feminism as their focus. But we were looking at the influence of these women artists. For instance, Judy Pfaff's, with sculptural abstraction, she said to us: "I was never included in any of these early feminist shows because I did abstract art." We were interested in looking not only at content, but looking at what the legacy of these various artists is.

With the second book, it was how these young women artists took this legacy and made it their own. I would say that's the connection between the two books.

Talk about how feminism has evolved or shifted and some of the tensions within what that term means?

I would hate to be quoted on any of that, because I might be skewered, but I would say for us--I'll just elaborate what I said earlier--is that we were much more interested in looking at these things in the bigger art world and not just artists that were focused particularly on feminist content. For instance, Marina Abramovic was raised in a communist country. She was in art school, and she didn't know about the feminist movement. She was raised by parents in the army. She was raised in a much more equal country, with a sense of equality back then. Her work is about something else. It's about pushing the body and the limits. It's not about questions of male and female. We were interested in including her because she is a performance artist.

You know Vito Acconci and Chris Burden. She's of their generation, but she's the only one still doing performance and doing very rigorous, painful performances, which is interesting. We feel this is what sets our book apart. We're not trying to answer or even define notions of feminism. We're looking at women's place, women's influence, and women's access to power in the art world.

Talk about those institutional dialogs around feminism? Have they shifted since the 90s?

People are becoming more aware of them, but you just need to look at our charts. Institutions are still at 24% for solo shows for women. I say, MOMA has given these two women artists retrospectives, but overall, they're pretty pathetic on how much they show women. We need to continue to be aware and point it out. I was just at the Yale Art Gallery. I walked in. I walked through. I thought it was really terrific. I got to the end of it and thought: Oh, from what I can remember, they had four women artists there.

To me, it is an awareness. We have not reached that place. We're certainly on par with the Senate. It's 20% female, so we're on par with that. But to me, the really telling disparity is that 50% of people coming out of MFA programs, give or take, are female. Then they go into the professional world and their chances are cut in half.

That's horrifying. I'm interested in a question around region. So many of the institutions you are talking about are the big, New York players. Do you get a sense that in the Midwest or the West or even LA or San Francisco that those numbers are different?

I can't speak to that. Maybe on the panel, Cathie Opie will talk about how it is in California. One of the schools we looked at was UCLA. From early on, they had as many women as men. Our speculation is that Mary Kelly ran that program from early on. It gets back to this thing: Let's just be aware of it. Let's just look at the numbers.

Until you look at what the curators are doing, I think it starts to get a little personal. One writer, who was in our audience and also teaches, she said an interesting thing would be to look at who got written about in the Whitney Biennial and who were the writers and where was the writing done? There are a lot of places to look at and threads to see who is being written about, who is doing the writing and where is the writing showing up.

I don't want too much focus on these statistics, because it's a small segment of our book. Most of our book is looking at these 24 artists.

What do the discussions of the individual artists look like?

Each of us did 6 essays. I wrote about Kate Gilmore. She's been in the Whitney Biennial and done things for Creative Time and gotten all kinds of awards. She currently doesn't have a gallery in New York. There is some writing, but there is no monograph on her. So, I interviewed her so there could be a primary source in this book. In some cases we didn't.

For us, it was a mix of biographical and critical and tying them into these themes and the ideas of what we're doing. Kate, for instance, does have a relationship to notions of feminism. She is a performance artist/video artist. She sets up challenges for herself, like kicking her way out of a box and climbing up this panel type thing that she did for the Whitney. She does it in high heels and a tea dress, playing with these ideas of fashion and limitations imposed on women.

Everybody has their own style. Nancy and Eleanor are critics. Helaine and I are curators. The first time we started writing, Helaine and I were used to writing a little bit different way. Like, oh, can you really say that? It's important to all of us not to get caught up in art speak and write clearly and convey an understanding of what the artist is doing and trying to do.

Over the decades you cover, there have been such huge shifts in terms of institutional support for the arts. How has the function of art shifted over these decades?

I don't know. I can only talk about my own experience. I came across a letter right after I moved to New York City in 1992. The Guggenheim had reopened, and the Guggenheim was something that the Guerilla Girls and WAC had really gone after. They were so male dominated and pro-male. I remember, I went up to the opening. I couldn't believe how few women were represented. It was shocking. I went home and wrote an essay and sent it off to the New York Times, and it got printed as an Op-Ed. I just reread it. I'd kind of forgotten about it over the decades. It's disappointing in a way that I was railing about the same things in 1992 that we are now. I don't want to say we're railing about them, but that we're aware of.

To me, that's the most important thing--that we're continually having the awareness, until we integrate that awareness into all the upper echelons, into the curators and directors. There is a curator in England who is saying that maybe they should instigate a quota system. Certainly, we wouldn't want to do that, but I think it gets back to awareness, if that makes sense.

What we want to focus on in these books are the accomplishments of these women. When we first came out with this book, it was selected as one of the top art books of the year. Even the word canon was used; here is a list of these artists. We were in no way trying to make a canon of the top 24 young women artists working today. We were trying to work internationally. We were trying to work across media and styles and give a whole range and spectrum. To me, that's the strength of the book. These other things give it a framework, but we're looking at what these artists are doing and how important they are.

This free panel takes place July 30 at 12:30 p.m. at Anderson Ranch. Wait list tickets will be available at the door.

By Michelle Dean

November 6, 2013

Like other realms of the culture, the visual arts are, at the moment, a male-dominated profession. A recent book put together by arts scholars, entitled The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium, records the same kind of problem you often hear women writers complaining about: in spite of the fact that MFA graduates are overwhelmingly women, it’s men who get the crucial solo exhibitions at galleries which can make or break an artist’s career. The Reckoning seeks to correct this by recognizing the work of 25 young female artists who are breaking new ground, these days. Here is a sampling of their work.

Tracey Emin, "Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995" (1995)

Tracey Emin is an English artist whose work is often called “confessional.” Her most famous work includes the above installation of a tent, called Everyone I Have Ever Slept With. (The names of said people are appliquéd on the inside of the tent.) If this sounds like a euphemism for all the people Emin has, well, had sex with, it isn’t, quite: her grandma’s name is on there, for example. The original tent was destroyed in a warehouse fire, in 2004; she’s never recreated it.

Catherine Opie, "Jake" (1991)

Catherine Opie’s work with photography is famed for its treatment of identity, and queer identities in particular. She made her name with portraits of the queer and trangender people she knows in Los Angeles. “Few artists of her generation,” the New York Times wrote of her 2008 retrospective at the Guggenheim,”have as consistently and brilliantly shown queerness to be the capacious category that it is.”

Ghada Amer, “Le champ de marguerites,” 2011)

Ghada Amer once traded one of her paintings for a green card. She works with embroidery and watercolor to create the kind of gorgeous canvas you see above, and her use of mixed media is politically motivated, as she reiterates in her artist’s statement to the Brooklyn Museum:

The history of art was written by men, in practice and in theory. Painting has a symbolic and dominant place inside this history, and in the twentieth century it became the major expression of masculinity, especially through abstraction. For me, the choice to be mainly a painter and to use the codes of abstract painting, as they have been defined historically, is not only an artistic challenge: its main meaning is occupying a territory that has been denied to women historically. I occupy this territory aesthetically and politically because I create materially abstract paintings, but I integrate in this male field a feminine universe: that of sewing and embroidery.

Jane and Louise Wilson are British sisters who work together. (I suppose that means this list technically contains 25 artists, but oh well.) They love abandoned buildings; the above video shows their work with Orford Ness, a British military test site.

Janine Antoni, “Lick and Lather,” 1992

Janine Antoni’s work has been said to blend performance with sculpture. What that means, in plain English, is that she likes to fashion her work in more creative ways than simply using her hands. For example, in her latest work, she licked the chocolate bust of herself, above, to create that mottled effect. She has also mopped the floor with her own hair.

Cecily Brown, “Sweetie,” 2001.

Cecily Brown’s paintings, particularly of late, are often both abstract and “figured,” in the sense that you can sometimes make out human figures in them.

Julie Mehretu, “Stadia I” 2004.

Julie Mehretu, who hails from Ethiopia, often sees her work called “architectural.” One reason for that is the way her paintings contain layers, and specifically often recall blueprints. “I don’t think of architectural language as just a metaphor about space, but about spaces of power, about ideas of power,” she once told an interviewer.

Detail from Pipilotti Rist, “Ever is Over All” (1997)

Pipilotti Rist, who is Swiss, likes to project moving images on walls. Many of them are lush landscapes of flowers, and they are always saturated in bright colors. The effect is beautiful, but almost too beautiful, even disorienting at times, though always kind of comforting. The New Yorker‘s art critic, Peter Schjedahl, has called her an “evangelist of happiness.”

Cao Fei, “UN-Cosplayers” (2006)

Cao Fei, a Chinese multimedia artist, does work that blends the old and new world with our hyper-fast culture. The above photograph, from herUN-cosplayer series, pretty much says it all.

Lisa Yuskavage, “Small Morning” (2005)

Lisa Yuskavage is known primarily for her female nudes. Like the above, they are always markedly voluptuous. And like Pipilotti Rist, she loves popping color. There’s also, generally, a lot of fruit, to signify fertility.

Justine Kurland, “Waterfall, Mama Babies” (2006)

Justine Kurland’s photography tends to focus on themes of escape, and of idyll, and she’s been called romantic because of it. She made her name with a series of photographs of female nudes in American countryscapes, particularly Western countryscapes. (Kurland hails originally from Poland but now lives, like almost all the artists here, in New York.)

Kara Walker’s silhouette panoramas tell stories of the cruelties and excesses of racism. Her work is disarmingly pretty to look at; it’s when you scrutinize the story that the images are showing that you come to see the darkness of them. Her theme is race. As the New York Times once put it, “It dominates everything, yet within it Ms. Walker finds a chaos of contradictory ideas and emotions. She is single-minded in seeing racism as a reality, but of many minds about exactly how that reality plays out in the present and the past. For her the reliable old dualities — white versus black , strong versus weak, victim versus predator — are volatile and shifting. And she uses her art — mocking, shaming, startlingly poignant, excruciatingly personal — to keep them this way.”

Liza Lou, “Kitchen” (1991-1996)

Liza Lou works not with paint, but with beads. Her most famous work is the above Kitchen, which took five years to complete. It gave her tendonitis. It also upset all her art teachers. But in the end, she was awarded a genius grant for her work, and continues to work in beads now.

Wangechi Mutu’s most famous pieces are collage. She likes to rework images from magazines into work that explores the nature of the body. “My work is often a therapy for myself — a working out of these issues as a black woman,” the Kenyan-born, Bed-Stuy-dwelling artist told New York recently, “And a way of allowing other black women to work through this kind of stigmatization as they look through the images and feel how distorted or contorted they might be in the public eye.”

Andrea Zittel, “Rough Furniture” (1998)

Andrea Zittel’s work is a little hard to describe in language. One of her first projectsinvolved renting a Brooklyn storefront and raising chickens in it. From there she moved on to a kind of furniture-building that was heavily inflected with sculpture. She has also built islands. The way art critics typically sum her up is as conducting an “investigation of fundamental aspects of contemporary domestic and urban life in Western society.”

Katarzyna Kozyra is a Polish video artist whose work has caused considerable controversy in her home country. She has been known to film horses at the moment of their death, for example, never a way to endear yourself to PETA sympathizers. She has also snuck into male bathhouses, disguised as a man herself, and filmed the ablutions performed therein. The above video, The Rite of Spring, uses time-lapse photography and elderly naked bodies to recreate the famous ballet of the same name.

Kate Gilmore, “Love ‘em, Leave ‘em” (2013)

Kate Gilmore’s work often focuses on themes of mess and destruction. She has, for example, in the past invited women to come into the pristine Pace Gallery and throw some clay around; other videos of hers involve breaking through walls. In Love ‘em, Leave ‘em, whose results are pictured above, she carried vases and pots filled with paint up these steps, and then let them shatter.

Mika Rottenberg, from Argentina, does video installations in which she casts unusual-looking women — another way of putting that might be “striking-looking women” — and then has them perform the kind of tasks which question the nature of labor and capitalism. You can see a good sampling in the YouTube video, above.

Yael Bartana’s And Europe Will Be Stunned, a video installation, was a sensation at the Venice Biennale a few years ago. It consists of three films that tell the (fictional) story of a Jewish repopulation of Poland. Israeli by birth, she generally explores themes of Jewish identity.

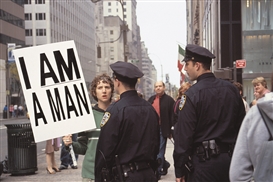

Detail from Sharon Hayes, “In the Near Future” (2009)

Sharon Hayes was and is deeply involved in activist politics, so her work, which typically combines performance and installation, is often explicitly political. Her art often comments on queer and identity politics in particular, and the way in which slogans interact with people’s need to belong.

Tania Bruguera, “Untitled (Havana)” (2000)

Tania Bruguera is a Cuban installation and performance artist. As perhaps befits someone from a country with a troubled political history, she’s interested in the uses and nature of power. The art critic Eleanor Hartley once wrote of her work, “‘In Bruguera’s world, concepts like freedom, liberty and self-determination are not abstract ideals, but achievements that write their effects on our physical forms.” The installation pictured above, for example, was shut down after a single day by Cuban authorities, because it seemed to them to be a (subversive) commentary on the political situation there.

Natalie Djurberg is a Swedish video artist. She likes to work with clay in particular, and her pieces tend to be oddly reminiscent of fairy tales.

Teresa Margolles, “Muro Ciudad Juárez,” (2009)

Teresa Margolles, a Mexican installation artist, uses her work to address the violence of Mexico’s drug war. In the above installation, a wall with bullet holes shows the extent of the violence. In another work, she had the floors of an exhibition space mopped with the water used to wash corpses in the morgue.

Klara Liden’s work often responds to architecture. In the above still from the video The Myth of Progress (Moonwalk), Liden herself moonwalks — yes, the Michael Jackson maneuver — through New York City’s streets at night.

The 30 Best Art Books of 2013

December 12, 2013

The work delves into the accomplishments of 24 international women artists born in the years following 1960 and serves as a follow-up to Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal and Sue Scott's 2008 book, "After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art." With themes like "Bad Girls" and "Domestic Disturbances," the publication appeals to radical feminists, art history buffs and anyone who cringed at Ken Johnson's remarks about female artists this year.

10 Women Artists of the New Millennium You Should Know

By Katherine Brooks

November 4, 2013

Shirin Neshat (Photo by Selin Alemdar/Getty Images)

In 2008, four female authors gathered together to address a decades-old question, once posited by art historian Linda Nochlin: "Why have there been no great women artists?"

The authors sought not to reaffirm the implied statement -- that, historically, men have dominated the world of art. Instead Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal and Sue Scott opted to methodically explore the new reality of the art realm after the feminist movement, exploring the growth and success of women in the field, and ultimately tossing Nochlin's question out the window entirely.

The result was After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art, a publication dedicated to the careers of 12 influential women artists working in the late 20th century, ranging from Louise Bourgeois to Shirin Neshat to Marina Abramovic. Through analysis of their works' critical success, market value and institutional support, Heartney and company reveal the progress women artists have made since the 1970s, adding to a foundation of scholarship that stands to push Nochlin's question into extinction.

"The battles may not all have been won," the authors wrote. "But barricades are gradually coming down, and work proceeds on all fronts in glorious profusion."

While After the Revolution paid homage to an earlier generation of women in art, the book only touched on the channels necessary to project the progress of predecessors onto the hordes of emerging women artists entering the field at the time. So, nearly five years after the publication of their first tome, they're analyzing how the radical works of Cindy Sherman and Kiki Smith have laid a foundation for a new age of women artists in The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium.

The work delves into the accomplishments of 24 international women artists born in the years following 1960. Organized according to four themes -- "Bad Girls" who explore unconventional notions of gender and race, artists who focus on "History Lessons" that take into account the role of the self and globalization, "Spellbound" artists whose work leans toward the irrational and surreal, and women who take on issues related to the home and family in "Domestic Disturbances" -- the work stands to show that women have not only invaded the canonical space once reserved primarily for men, but they've also actively propelled the world forward, using media like video and performance to expand our concept of art.

Heartney et al recognize that there is still room for growth, particularly in terms of women's gallery representation and the number of solo shows headlined by female artists in museums. However, the four authors focus less on the numbers and more on the nature of the art being made by women, agreeing with critic Holland Cotter's famous words, "Feminist Art... is the formative art of the last four decades."

In honor of the book's release last month, here's a preview of the women profiled in The Reckoning.

Wangechi Mutu, This you call civilization?, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects

Exhibition view of The Parade: Nathalie Djurberg with Music by Hans Berg, New Museum, New York, 2012. Courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery, New York, and Giò Marconi Milan. Photo by Benoit Pailley.

Mika Rottenberg

Mika Rottenberg, Still from Cheese, 2007. Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, and Nicole Klagsburn Gallery, New York.

Katarzyna Kozyra

Katarzyna Kozyra, Cheerleader, 2006. Production photograph by Marcin Oliva Soto.

Sharon Hayes

Sharon Hayes, In the Near Future, 2009. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin.

Yael Bartana

Yael Bartana, Trembling Time, 2001. Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, and Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv.

Cao Fei

Cao Fei, RMB City 4, 2007. Courtesy of the artist, Lombard Freid Gallery, New York, and Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou.

Kate Gilmore

Kate Gilmore, Standing Here, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

Klara Liden

Klara Liden, S.A.D., 2012. Photo by Farzad Owrang, courtesy of Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York.

Tania Bruguera

Tania Bruguera, The Burden of Guilt, 1997–99. Image courtesy of Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas.

photo by the author for Hyperallergic

This book by Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal, and Sue Scott explores the state of female artists today. The premise may be wide and sprawling, but the book is inspiring after you read and understand the different strategies that women have engaged with to make their mark on art. By bringing together very established artists with emerging ones, the book can feel like a mixed bag, but it’s exactly that exchange between history and the future that makes this volume exciting. The charts of female participation in major exhibitions around the world make you realize there’s a still long way to go until we reach gender parity in the art world, but, between you and me, I think books like this will ensure we get there … eventually.

Fine Arts - Review

By Tina Chan

March 2014

Library Journal Review

The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium

Prestel 2013 256p. illus. bibliog. index. ISBN 9783791347592. pap. $39.95. Fine Arts

The work of 24 international female artists born after 1960 is covered here by the co-authors of After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art (2007). Heartney (contributing editor, Art in America), Helaine Posner (Neuberger Museum of Art), Nancy Princenthal (former senior editor, Art in America), and independent curator Sue Scott organize the work into four sections—"Bad Girls," "Spellbound," "Domestic Disturbances," and "History Lessons"—and analyze how feminism influenced artists Janine Antoni, Jane and Louise Wilson, Cao Fei, Wangechi Mutu, Mika Rottenberg, Cecily Brown, and Pipilotti Rist and how their work impacts visual and performance art. The women confront issues of gender and race, home and family, history and globalization. While an extensive bibliography for general reference is included, for the individual artists, a bibliography contains their monographs, solo and group exhibition catalogs, and studies. Succinct essays on each person and complemented by color and black-and-white images of their output.

VERDICT

Suitable for anyone who wants to learn about contemporary art by women, as well as undergraduate and graduate students, scholars, and researchers studying visual and performance art.

Female Artists are a Force to be Reckoned With

By Lori Zimmer

February 19, 2014

The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium by Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal and Sue Scott, is the new quintessential volume that illustrates the importance of female artists in visual culture. The book focuses on the work of 24 hand-picked female artists, born after 1960, that have pushed beyond the stereotype of 1970s “feminist art” and have asserted themselves as influencers in the modern art world. With approachably written chapters on each of the women, the authors define these artists’ important roles in the shaping of contemporary culture and art.

The Reckoning is the powerful follow-up book to the authors’ seminal After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art, which gives an introduction and overview to 12 female artists from Louise Bourgeois to Dana Schutz, who helped to push and shape the role and perceptions of female artists in the art world. The Reckoning takes a step further, examining a younger generation of women artists specifically who live in cultures affected by the globalization of the contemporary art world. Each of the women was chosen organically by the authors as discussions ensued about artists’ as well as common themes and their various methods of creating work. Rather than defining each section by the artists’ nationality, medium or age, the resulting list was split into four highly unorthodox categories; Bad Girls, History Lessons, Spellbound and Domestic Disturbances.

Katarzyna Kozyra, Cheerleader, 2006. Production photograph by Marcin Oliva Soto.

Although the artists often intersect one or more of the categories, they were loosely assigned to each to help illustrate how sexual identity, politics, internal experience and pleasures and pressures of domestic life are explored through their work. The Bad Girls chapter, penned by Eleanor Heartney, delves into the hot button issue of sex and sexuality, posing the eternal question of whether pornography and sexually explicit imagery is empowering or a form of male violence against women. The artists chosen for the chapter embrace the former, using the female body and sex as a method to attack the traditions of male gaze and take ownership back so to speak. Possibly the most famous Bad Girl of them all, YBA artist Tracey Emin is of course featured, as well as Ghada Amer, Cecily Brown, Mika Rottenberg and Wangechi Mutu, who use sex and the body to assert power in their imagery. Polish critical artist Katarzyna Kozyra plays on the idea of gender in many of her videos, using the fringes of society like drag queens, midgets (specifically using the politically incorrect term), amputees, body builders and naked men and women to illustrate her theories of the malleability of masculinity and femininity, gender and violence. Pushing between male and female roles, her piece Cheerleader from the In Art Dreams Come True series features Kozyra as the head cheerleader cavorting in the male locker room, only to strip at the end to reveal herself as a naked boy (with the help of prosthetics).

Mika Rottenberg, Still from Cheese, 2007. Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, and Nicole Klagsburn Gallery, New York.

Cao Fei, RMB City 4, 2007. Courtesy of the artist, Lombard Freid Gallery, New York, and Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou.

The chapter Spellbound, by Nancy Princenthal, refers to the stereotype that women are wistful, dreamy and undirected, with a stable of artists who manipulate the symbolism and trance-like imagery to create powerful work that criticizes oppression from male society. With roots in Surrealism, artist such as Janine Antoni, Pipilotti Rist, Lisa Yuskavage, Jane & Louise Wilson andCao Fei use dream-like imagery, flowing cloth material, cartoon influences and the like to pick up where the great Louise Bourgeois left off, creating fantastical imagery with an underlying current of gender. For example, Swedish born Nathalie Djurberg uses materials that could be called child-like – crude Plasticine and clay – to make stop animation videos that border on the humorous. Because of the nature of her materials, Djurberg’s characters, both animals and humans, suffer almost comical violence, as arms, legs and penises are cut off, flesh stripped away and eyes gouged out in a frenzy bringing together eroticism, cynicism and dangerous behavior, as if seen through the eyes of an uncomprehending child.

Exhibition view of The Parade: Nathalie Djurberg with Music by Hans Berg, New Museum, New York, 2012. Courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery, New York, and Giò Marconi Milan. Photo by Benoit Pailley.

Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg, Tiger Licking Girl's Butt, 2004. Courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery, New York, and Giò Marconi Milan.

Sue Scott’s chapter, Domestic Disturbances, delves into how the issues of home and family weigh upon female artists. A duality of resisting and embracing domestic life is a theme that runs throughout the work of many contemporary female artists’ as roles, work life and culture have changed over the past 50 years. Leaving the extremism of women’s liberation and adjusting to a more modern and semi-balanced present, these artists explore the allure and propulsion of domesticity, thinking of the feeling of “home” as both welcoming and confining. The work of artistKate Gilmore opens the chapter, a video artist who often casts herself as the female protagonist thematically working against something, and involving physical exertion. Placing herself at the center of her art, her most iconic piece was debuted at the Whitney Biennial of 2010. In Standing Here, Gilmore literally fights her way up a constructed chute, emulating an “upright birth canal” that she claws her way to the top of, symbolically becoming a woman born into the art world.

Kate Gilmore, Standing Here, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

The Reckoning’s final chapter, History Lessons by Helaine Posner features artists who pay homage, or reference the great feminist artists of the 1970s in their work. Yael Bartana, Tania Bruguera, Sharon Hayes, Teresa Margolles, Julie Mehretu and Kara Walker each poignantly cull from women’s struggles throughout history to inspire their works. Pulling from the 1960s protest movements, Sharon Hayes bases her performances and videos on this idealism of speech, using their methods of marching and demonstrations to communicate private expressions of longing and desire. Together, she fuses history with self-expression seamlessly.

Yael Bartana, Trembling Time, 2001. Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, and Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv.

Sharon Hayes, In the Near Future, 2009. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin.

Through the narrative of each category, the authors bring a voice to individual artists along with easy to read graphs and data that compare and contrast the number of female artists to males in MFA programs, museums and galleries. Interestingly, the authors found that these numbers were closely relatable to trends in society, like the comparable percentage of female to male solo shows as there are men to women in the United States Senate. The fascinating volume gives a modern voice to women artists beyond the days of 1970s feminism, bringing us into the twenty-first century when women have become an integral part of the art market. With the ink just dry on The Reckoning, the quartet is already thinking about how to expand to a third book in the series.

After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art

By Patricia Briggs

Rain Taxi, Review of Books

Visual Art Critics Union of Minnesota (VACUM)

Vol. 13 No. 1, Spring 2008

After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art offers a series of original essays devoted to a wonderful list of artists—Louise Bourgeois, Nancy Spero, Elizabeth Murray, Marina Abramovic, Judy Pfaff, Jenny Holzer, Cindy Sherman, Kiki Smith, Ann Hamilton, Shirin Neshat, Ellen Gallagher, and Dana Schutz, written by prominent critics, authors, and curators Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal, and Sue Scott. This book, as well as the exhibition at Dorsky Gallery in Long Island and a public panel at The New School which accompanied it, grew out of an experimental spirit that genuinely seeks to stake out new terms of inquiry on the topic of contemporary women artists. The authors are well aware of the fact that gender, the body, and sexuality have become the stock and trade of a whole generation of artists who work with these themes and concerns without necessarily politicizing them in feminist terms. How to approach the issue of women artists in today’s climate? What questions do we need to ask today? One pressing yet familiar question arises in the introduction of this book: do women artists today stand on a level playing field with their male counterparts in terms of the attention they receive from museum and gallery curators—this being an indicator of their professional success and market value?

The status of women in the contemporary art world has obviously undergone enormous change since the early days of feminist activism in the arts. In 1971, Linda Nochlin, in a sense, investigated this question when she wrote her pivotal essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, and argued that institutional structures have created obstacles for women, leading to the devaluation of women’s art as a category. One legacy of the work of feminist scholars like Nochlin is that today’s women artists are able to succeed, even hold positions at the forefront of the art world. After all, didn’t Kara Walker, Julie Mehretu and Jenny Saville quickly gain prominence after making their debuts in the early 1990s? Does the meteoric rise of a handful of contemporary women artists really translate into women’s equality within the market overall?

While difficult to track, sales are a gauge for the professional success of artists, and the purchasing patterns of private and public patrons can be linked to solo exhibitions. Accordingly, the authors of After the Revolution carried out a study analyzing the number of male and female artists who received solo exhibitions in representative museums and galleries in New York City. Tracking an increase in exhibitions of women artist from the 1970s through the 1990s, the results of this study are nevertheless startling. During the 1970s influential galleries mounted solo exhibitions of women 11.6 percent of the time. During the 1980s the percentage increased to 14.8. The percentage increased to 23.9 during the 1990s, when it peaked.

Today, the percentage of solo exhibitions for women artists has slipped to 21.5 percent. The statistics on solo shows in New York City museums are slightly better overall for women artists, but they fall into the same pattern. During the 1990s, solo shows for women reached 30 percent; yet since the turn of the century this number has dropped, with women artists receiving only one out of four solo shows in New York City Museums. Some questions, it would seem, still need to be asked, and clearly some institutional obstacles are still in place for women artists.

The authors of After the Revolution might have stressed the obvious lack of curatorial parity and the attendant market value it implies in their study of the New York City art market by offering a rant about continued subordination of women artists. But they didn’t. Reminding us that being a woman continues to be an obstacle within the art market, the authors instead focus on the positive aspects of the more welcoming landscape for women in the arts today, where new—some might say post-feminist—outlooks have integrated women and issues of gender into the dominant narratives and conceptual frameworks of art history and art criticism. In essence, they attempt to embrace this new conceptual field, where feminist analysis is not prescriptive, does not stereotype, is not essentialist, and does not impose an intrusive language of theoretical hocus-pocus.

But how can this be done? How can these authors embrace a new conceptual field that has been reformulated by feminist and postmodernist concerns while using the (now) well-worn category “women artist”? It’s a bit like fitting a round peg into a square hole. Aware of the theoretical difficulties—the potential to stereotype and essentialize that comes with the category “women artist”—Heartney et al. argue for the value in simply “look(ing) back at the last thirty-five years of art-making by a small number of key figures to gain a better understanding of how artworks by women have shaped the art of our time.” It is useful—“illuminating”—they argue, to simply look at the accomplishments of key figures with a fresh eye and to “take stock”.

These are interesting propositions, but carrying them out proves difficult. This is the case for example with Nancy Princenthal’s essay on Elizabeth Murray and Helaine Posner’s essay on Ann Hamilton. So mired in description and listing of works, these essays dull the luster of the artists’ projects rather then making them shine more brightly. Thus, some attempts to offer a fresh way of looking (that is, non-essentializing) in After the Revolution do not produce the hoped-for “illumination.”

However, many of these essays do offer enlightening views. Posner’s essay on Nancy Spero weaves a lively account of Spero’s personal views, her life, and the political and critical context for her work into a rich narrative that allows the reader to see the artist’s aesthetic development—her growth from a position of protest toward a utopian point of view—in a new light, at the same time that it ties Spero’s figurative style with artists like Kiki Smith and Lesley Dill, to whom she is normally not compared. Sue Scott’s essay on Dana Schutz presents an artist who is young enough that many readers may not be familiar with her work. Schutz is a figurative painter who might more immediately be contextualized within the tradition of expressionist painting. However, by placing the artist’s brightly colored figurative tableaux within the context of women’s art history, Scott links them with issues of identity and embodiment in ways that might otherwise be missed.

Particularly insightful is Heartney’s essay on Cindy Sherman, where many of the artists’ projects are discussed in light of their original commission for fashion magazines. Heartney reviews the key theoretical concepts linked to Sherman’s work during the 1980s and the 1990s, yet points out that the artist’s critical reception often did not correspond with her own thoughts about her work. Suggesting instead an impulse toward play that corresponds more closely with Shermans’s own remarks about her creative process, Heartney pushes aside the now canonical critical veil which has fossilized around Sherman’s photographic projects. Heartney’s revision of Sherman’s well-known images in a sense makes them new again, and her success here advances the idea that established figures like Kiki Smith and Cindy Sherman, whose work has received great attention over the years, are truly ripe for fresh eyes and a fresh read.

In short, all the authors assert, as Nochlin herself does in the foreward, that:

"Whether they are “great” or not is beside the point. There is something stodgy and fixed about the very word “great,” something that smells of the past and tradition…For the women artists considered in this book, it is vitality, originality, malleability, an incisive relationship to the present and all it implies…that is at stake, not some mythic status that would confine them to a fixed, eternal truth."

There can be no doubt that over the past four decades, feminist criticism and the work of women artists have had a revolutionary impact on artistic practice. Today art takes shape, as these authors argue, “after the revolution.” With this book, they set out to reposition our approach to contemporary art in light of this post-revolutionary context. Although a few of the essays included in After the Revolution never quite get lift-off, one cannot help but be impressed with and inspired by these authors’ gutsy attempts at proposing a new method and a new way of contextualizing the work of contemporary women artists.

Book Review: The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium

By Sally Deskins

January 24, 2014

Twenty-five unshackling international female artists born post-1960 are presented in a visual whirlwind in The Reckoning: Women Artists of the New Millennium (2013, Prestel) by the four authors of After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art (2007): Eleanor Heartney, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal and Sue Scott.

The 2007 edition examined the careers of twelve female artists since the 1960s feminist movement and the transformations of their influence, commercial appeal and level of institutional support. In this edition, the four authors embark upon four themes asking; “After the revolution comes the reckoning… Exactly what has been accomplished, what changed?” (Linda Nochlin in the introduction to the 2007 book).

Sections “Bad Girls;” “Spellbound;” “Domestic Disturbance;” and “History Lessons” provide a stellar illustration of the range and breadth of genius and novelty of the half of the population that society is still awakening to.

“Bad Girls” begins with feminism’s notorious sub-genre, sexuality. Author Eleanor Heartney examines the history of feminist thought on provocation and the male gaze, asking: “Are women who play with sexually suggestive images liberating themselves or succumbing to patriarchal prejudices?” Looking at contemporary exhibitions, popular culture and artists in the visual essay, Heartney then explores the often-mixed message via six who “engage with the body not as a fixed site of meaning but as a fluid component of ever-shifting identity” (23).

Ghada Amer’s colorful and enigmatic paintings, mixed media and installation using women “and the assertion of female agency through the unorthodox tool of pornography” (29) begin the conversation with clear intent.

Perhaps less expected is Cecily Brown, whose nude work is a bit more abstracted and gestural. As the author concludes, it is by her process she defies: “The point that Brown’s trajectory demonstrates, both as a painter and an artist, is that regardless of content or posturing, she succeeds in taking on the machismo of gestural painting on the canvas itself” (39).

The third pegged “Bad Girl,” the infamous Tracey Emin, overtly presents, via installations, mixed media and neon lights frequently using text, “her tales of sexual promiscuity, rape, and abortion, with Emin’s experiences and the emotions they lay bare, especially for women” (41).

More playful, but nonetheless subversive, is the work of Katarzyna Kozyra, a leading representative of Polish Critical Art, challenging political issues and sexual expression. With intense, theatrical video art, Kozyra presents “a place where gender is literally a costume, where male mentors teach women how to be female… Kozyra’s post-gender world suggests that identity is something we perform, not something we are” (53).

More incredible insights are made with Wangechi Mutu, who “takes a cross-cultural look at the exoticized, eroticized, and demonized female body, particularly the black female body, as the repository of society’s fascination and fears.” (55) Mutu’s mixed media figures, adorned with African designs, flowers, and “wild” animal prints “literally erupt with life… She represents nature in our culture — a symbol of beauty, wonder, and power that the patriarchy both desires and fears” (57).

The last “Bad Girl” is Mika Rottenberg, known for her video installations that feature physically exceptional women employed in activities that are, the author fascinatingly reveals, both rational and bizarre, as she is concerned with “the way women’s labor has been marginalized and almost invisible throughout history” (61).

The “Spellbound” section examines six artists who exhibit the often-considered feminine trait of dreaminess, adding to it “a trusty tactic of subversion… finding this inclination a source of expressive strength” (69).